In a previous post, I paid homage to American jazz accordionist Frank Marocco, who grew up in the swing era and drew from the great American songbook throughout his career. Today’s post looks at the great Dutch accordionist Johnny Meyer, who preceded Frank Marocco by a generation and helped to establish swing accordion in Europe.

In a small park in Amsterdam near the Prinsengracht canal, across the street from an upscale “coffeeshop”, children play and shuffle through fallen leaves. Business as usual in the Jordaan, this rugged one-time working-class neighborhood. What makes this park stand out, even in a city like Amsterdam, are the watchful statues of old Jordaan’s favorite musicians.

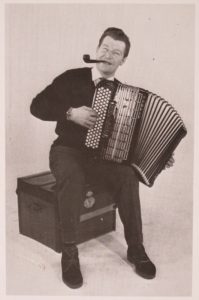

While these statues may only receive passing interest from today’s tourists and playground enthusiasts, I have come here to pay my respects to one of the earliest and greatest proponents of swing accordion in Europe, Johnny Meyer, forever chomping on his cigar and unleashing wild improvisational lines on his Accordiola button accordion.

While these statues may only receive passing interest from today’s tourists and playground enthusiasts, I have come here to pay my respects to one of the earliest and greatest proponents of swing accordion in Europe, Johnny Meyer, forever chomping on his cigar and unleashing wild improvisational lines on his Accordiola button accordion.

WHO WAS JOHNNY MEYER?

WHO WAS JOHNNY MEYER?

Johnny Meyer (alternately spelled Meijer or Meier) was born on October 1, 1912 in Amsterdam. He began to play accordion as a child and was playing in Dutch big bands before the Second World War. The immediate post-war years appear to have been fertile for Johnny Meyer and the liberating sound of his swing accordion, and he recorded many swing standards and received several accolades in the 1950s. Like so many other professional accordionists, Johnny Meyer’s recording output and performances after the golden years of the 1940s and ‘50s appear to have received a set back by the arrival of rock-and-roll in the early ‘60s.

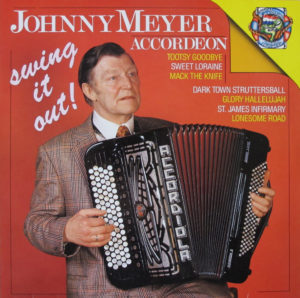

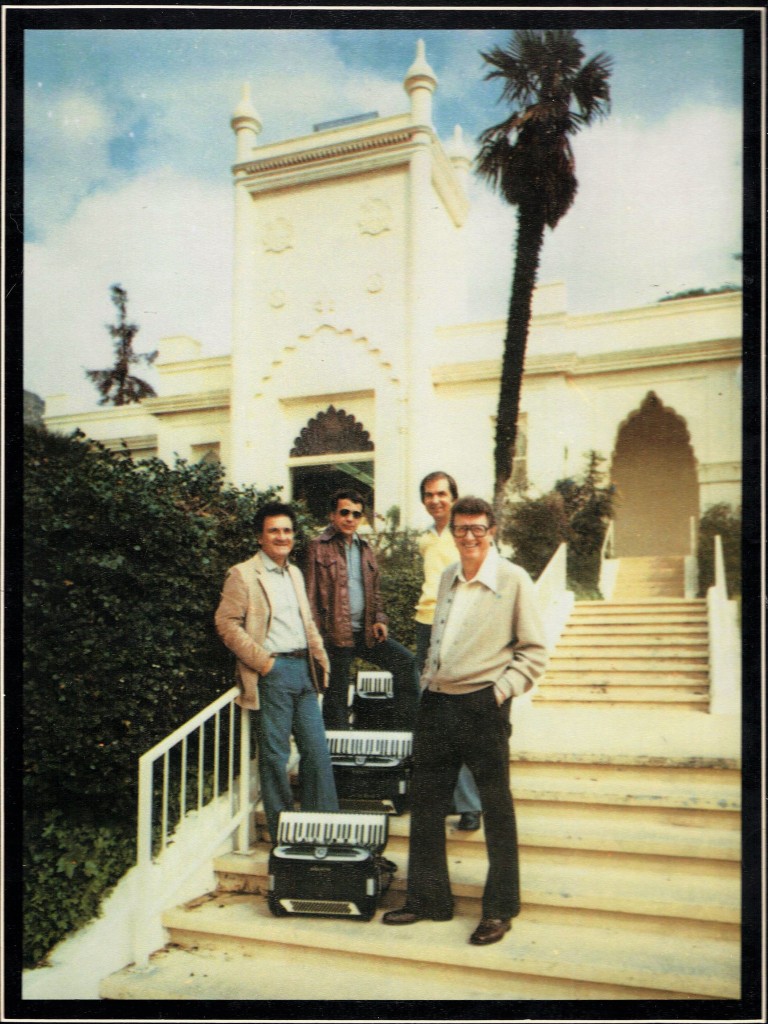

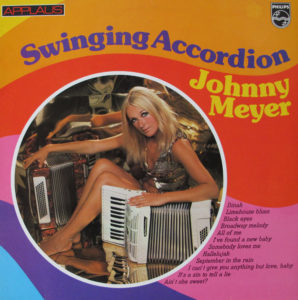

A compilation album from this later period, but featuring songs recorded from 1952-1957, illustrates his devotion to the swing genre – and indicates that the record label thought that it would sell better with a little bit of cheesecake ! Although he toured Europe, he is mostly known for performing within his home country. A lifelong musician, Johnny Meyer spent his final years playing occasional jazz gigs around Amsterdam. He passed away on January 8, 1992. See American jazz accordionist Art van Damme paying his respects at Johnny Meyer’s grave, which features a wonderful headstone carved like an accordion!

A compilation album from this later period, but featuring songs recorded from 1952-1957, illustrates his devotion to the swing genre – and indicates that the record label thought that it would sell better with a little bit of cheesecake ! Although he toured Europe, he is mostly known for performing within his home country. A lifelong musician, Johnny Meyer spent his final years playing occasional jazz gigs around Amsterdam. He passed away on January 8, 1992. See American jazz accordionist Art van Damme paying his respects at Johnny Meyer’s grave, which features a wonderful headstone carved like an accordion!

JOHNNY MEYER’S SOUND

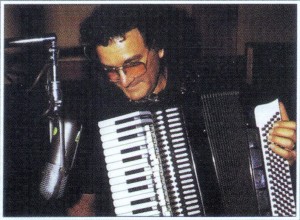

For me, Johnny Meyer’s style is firmly rooted in the swing era tradition of clarinetist Benny Goodman, one of the top performers from the era. This was the case for many early swing accordionists, since there were no jazz accordion precedents – no surprise then that Meyer’s solos bring Goodman to mind, or even pianist Teddy Wilson! An early example of Johnny’s mastery of the swing idiom can be heard in this recording of Tea for Two. Although the video was obviously recorded after the accompanying soundtrack, it is a delight to watch Johnny’s right hand glide effortlessly over the buttons of his keyboard as he executes smooth glissandi. This is used to great effect in the live video of Sweet Georgia Brown, where he alternates “Goodmanian” single-note lines with glissandi that erupt into chords, culminating in some seemingly impossible chord melodies (near the 2:30 mark)!

It is important to note that Johnny Meyer remained faithful to the swing style through the end of his life (in addition to recording more “popular” music too), which can be contrasted with Benny Goodman, who did make an excursion into bebop territory when it became more fashionable. Nevertheless, Johnny Meyer apparently had a sense for more modern harmonies, as he beautifully presents in the introduction to Polkadots and Moonbeams, recorded in 1988.

Thankfully, Johnny Meyer left behind a considerable discography for new fans of jazz accordion to discover. A good introduction to his swing era recordings can be found on Volume 3 (aka “Rebop Continental”) of the 4-CD set “Squeeze Me: The Jazz And Swing Accordion Story” (Proper Music).